Social Security was never designed for sustainability. The “Ponzi” element was there at the beginning: early recipients received HUGE benefits over their contributions, but as the population matured, that ratio of what working taxpayers put in compared to what they received in benefits decreased.

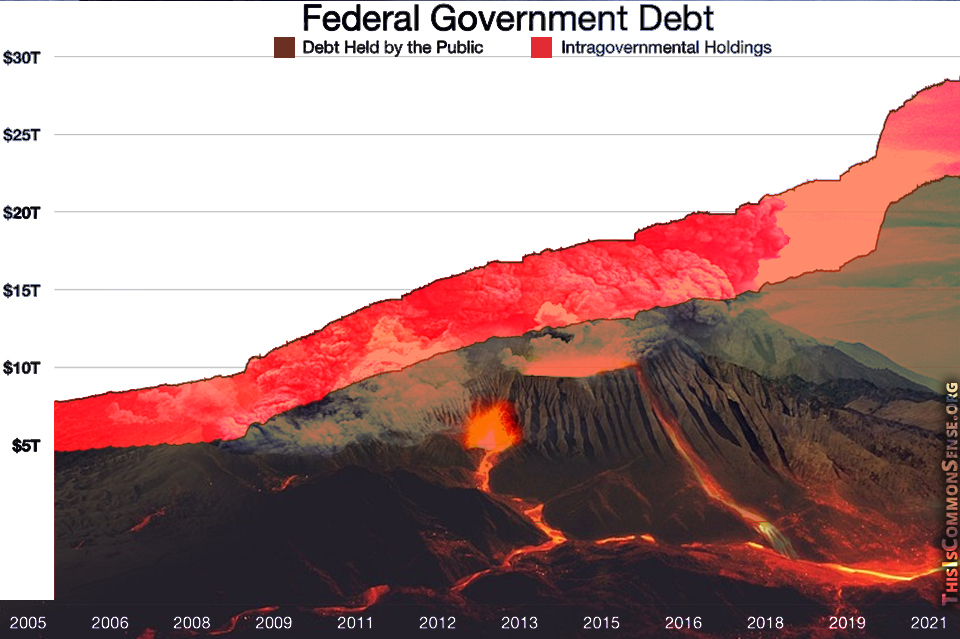

Further, because there never was a “lock box” much less any investment of funds — it was always a transfer scheme — as the system matured it hit the point of financial default. Back in the 80s this was fixed by raising the taxes on working people.

And then the kicker: with the rate of reproduction in the U.S. falling like Sisyphus’s rolling stone, the ratio of taxpayers to subsidized retirees went in the wrong direction. The folks assigned to keep track of the system’s finances predict that a major insolvency moment occurs about a decade from now, a few years ahead of earlier predictions.

So what does Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman, of The New York Times opinion page, advise?

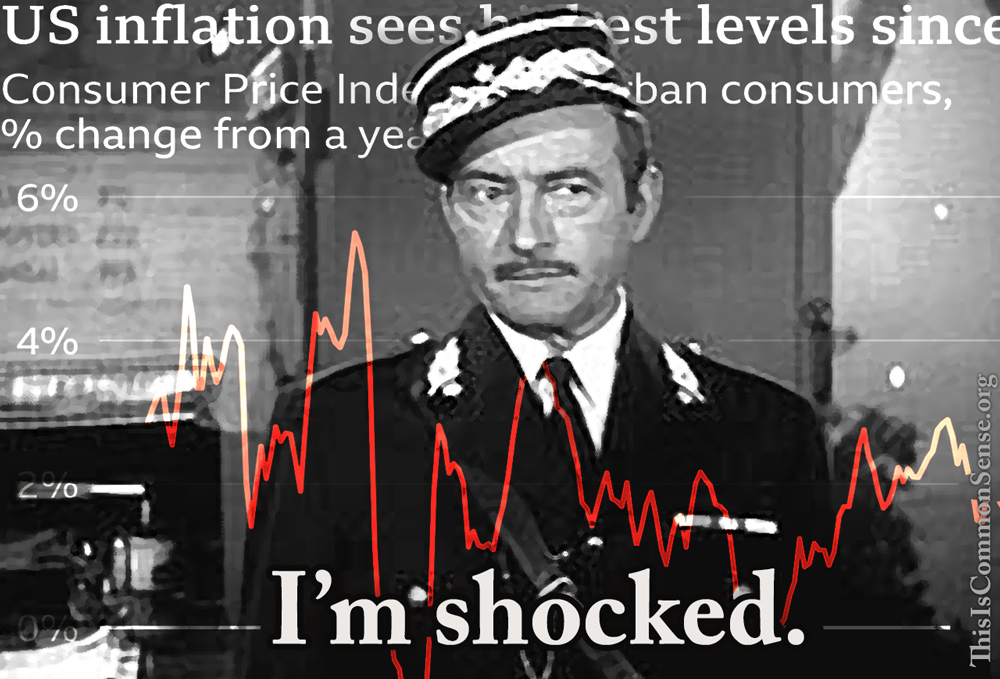

While we fret about the devastation that benefit cuts and tax hikes would cause, Reason’s Eric Boehm notes that Krugman doesn’t think the cuts are necessary. “First, Krugman says the CBO’s projections about future costs in Social Security and Medicare might be wrong. Second, he speculates that they might be wrong because life expectancy won’t continue to increase. Finally, if those first two things turn out to be at least partially true, then it’s possible that cost growth will be limited to only about 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) over the next three decades and we’ll just raise taxes to cover that.”

Hope over reason! And the progressive’s blithe acceptance of always-increasing tax burdens.

Serious people should confront facts … and avoid Krugman.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with PicFinder.ai and DALL-E2

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)