On January 7, 1940, the Finnish 9th Division completely destroyed the much-larger Soviet forces on the Raate-Suomussalmi Road, in a crucial battle during Finland’s Winter War.

Winter War

On January 7, 1940, the Finnish 9th Division completely destroyed the much-larger Soviet forces on the Raate-Suomussalmi Road, in a crucial battle during Finland’s Winter War.

In his whiny announcement, Governor Walz verged on apoplexy. “Those bumbling Somali fraudsters screwed everything up! The optics have gone to @#$%&!; citizen journalist, my [insert alternative grawlix here]! And Trump is mean!” Look, if you don’t believe me, I’ll fax you the transcript.

OK. I may be paraphrasing.

But I’m close. Associated Press reports his bitter comments on why the jig is up. Walz is waltzing out of the campaign because he can’t give it “my all” because of the “extraordinarily difficult year for our state” because of the latest revelations of how crappily and dishonestly he functioned as governor.

Walz said: “Donald Trump and his allies — in Washington, in St. Paul, and online — want to make our state a colder, meaner place.” These baddies “want to poison our people against each other by attacking our neighbors … want to take away much of what makes Minnesota the best place in America to raise a family.”

All very elusively allusive. What could Senor Real Man possibly be talking about? Why would any Minnesotan — say, an honest taxpayer — want to attack another Minnesotan — say, someone living high off the hog on the taxpayer dime, effectively taking money from the mouths of babes? Or a dishonest politician cooperating with and benefiting from just such massive taxpayer-funded fraud?

Don’t run, Walz. Don’t run. Stay right where you are.

So that prosecutors can find you.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with Nano Banana

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

See recent popular posts

Man’s concern is not with government; he should look on government as no more than a very secondary thing — we might almost say a very minor thing. His goal is industry, labour and the production of everything needed for his happiness. In a well-ordered state, the government must only be an adjunct of production, an agency charged by the producers, who pay for it, with protecting their persons and their goods while they work. In a well-ordered state, the largest number of persons must work, and the smallest number must govern. The work of perfection would be reached if all the world worked and no one governed.

Charles Dunoyer, De la liberté du travail (1845), David M. Hart, translator.

On January 6, 1907, Maria Montessori opened her first school and daycare center for working class children in Rome, Italy.

In 1912 on this date New Mexico became the 47th state of America’s United States.

On this date in 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered his “Four Freedoms” State of the Union speech, emphasizing vague “freedoms” that enabled government to usurp definable freedoms.

On January 6, 2021, lame duck President Donald John Trump gave a speech in Washington, D.C., aiming to rouse his supporters to pressure the U.S. Senate not to certify some states’ Electoral College votes in Election 2020, to address “election fraud.” Before his speech ended, some of his supporters (along with false flag agents) broke into the Capitol to set off one of the great political controversies of our time.

Sure, it’s an act of war.

Authorized by Congress? Not really, but that’s hardly unusual.

There is that 2020 indictment, unsealed by the U.S. Department of Justice during Trump’s first term, accusing Maduro and senior Venezuelan officials of conspiring with Colombian guerrilla groups (like the FARC) to traffic massive quantities of cocaine into the United States. This was updated in a superseding indictment unsealed over the weekend, which added Maduro’s wife, son, and others as defendants.

Specifically, the charges are:

Considering that Venezuela is a sovereign state and can have whatever drug policies or gun laws it wants, all this might seem a tad … ridiculous.

Most people, however, will likely be moved by two very different lines of thinking:

Is the effort coherent and compatible with other international military stances of the United States? Debatable.

How does it affect, say, the U.S. position on Taiwan? Will this encourage or discourage the People’s [sic] Republic [sic] of China?

One could argue both ways. As a successful demonstration of military might, it will likely dissuade the Chinazis. But if it turns world opinion against the U.S., the opposite will likely prove true.

Still, isn’t it hard to side with a dictator? I mean Maduro.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with Nano Banana

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

See recent popular posts

La spoliation ne déplace pas seulement

la richesse, elle en détruit toujours une partie.

Spoliation does not merely displace wealth; it always destroys a part of it.

Vilfredo Pareto, Les systèmes socialistes (1902 – 1903), Vol. II, p. 54, David M. Hart, translator.

On January 5, 1914, the Ford Motor Company announced an eight-hour workday and a minimum wage of $5 for a day’s labor.

The Minnesota fraud story did not just emerge in the last few weeks or months. It appears that before it became a predominantly Somali story it was dominated by one white woman.

Concerns about fraud in the federal child nutrition programs (tied to Feeding Our Future, a nonprofit sponsoring meal reimbursements for daycares and other sites) began emerging in late 2020, with formal flags and audits in early 2021. It became public knowledge through FBI raids in January 2022.

Aimee Bock, founder and executive director of Feeding Our Future, was indicted in September 2022; her trial occurred in early 2025, resulting in a guilty verdict on March 19. She’s awaiting sentencing as of January 2026, with recent asset forfeitures approved in December 2025.

(Notice that this was what civil asset forfeiture was originslly designed for: to confiscate goods used in crimes from convicted criminals. Not grabbing property from people not convicted of anything, as has been happening in these United States for far too long.)

Ms. Bock’s fraud scheme, often called the Minnesota daycare scandal due to involvement of daycares and child nutrition funds misused during COVID-19 (totaling about $250 million in fraud as counted up from court judgments). It’s described as one of the largest pandemic-era fraud cases in the U.S., involving fake meal claims, shell companies, and kickbacks. Over 90 people have been charged across related schemes, with dozens convicted.

Here is a timeline of developments in the story:

To check up on all this, consult The Sahan Journal timeline for pre-2022 details.

So who is Aimee Bock? A 2022 Star Tribune article noting that Bock filed for bankruptcy with her ex-husband in 2013 suggests she was previously married and divorced before the Feeding Our Future scandal emerged. Her ex’s name is not mentioned in any reports.

Ms. Bock is described as white/Caucasian in appearance and background. Reporting on the scandal frequently contrasts her with the majority of co-defendants, who were members of Minnesota’s Somali-American community (many first- or second-generation immigrants). Bock herself accused state agencies of discrimination against Somali-owned sites in pre-indictment statements.

Aimee Bock earned a Bachelor of Science in elementary education from the University of Minnesota Duluth in 2003. Public records and biographies list her residences in various Minnesota locations, including Duluth, Rochester, Burnsville, Cottage Grove, Rosemount, and Apple Valley.

She built her entire professional career in Minnesota, starting in early childhood education roles (e.g., daycare instructor, center director) and founding Feeding Our Future there in 2016.

As of 2025 reports she is 44- or 45-years old is consistently described as Minnesota-based, with at least 20 – 25 years of residence in the state.

Man’s concern is not with government; he should look on government as no more than a very secondary thing — we might almost say a very minor thing. His goal is industry, labour and the production of everything needed for his happiness. In a well-ordered state, the government must only be an adjunct of production, an agency charged by the producers, who pay for it, with protecting their persons and their goods while they work. In a well-ordered state, the largest number of persons must work, and the smallest number must govern. The work of perfection would be reached if all the world worked and no one governed.

Charles Dunoyer, De la liberté du travail (1845), David M. Hart, translator.

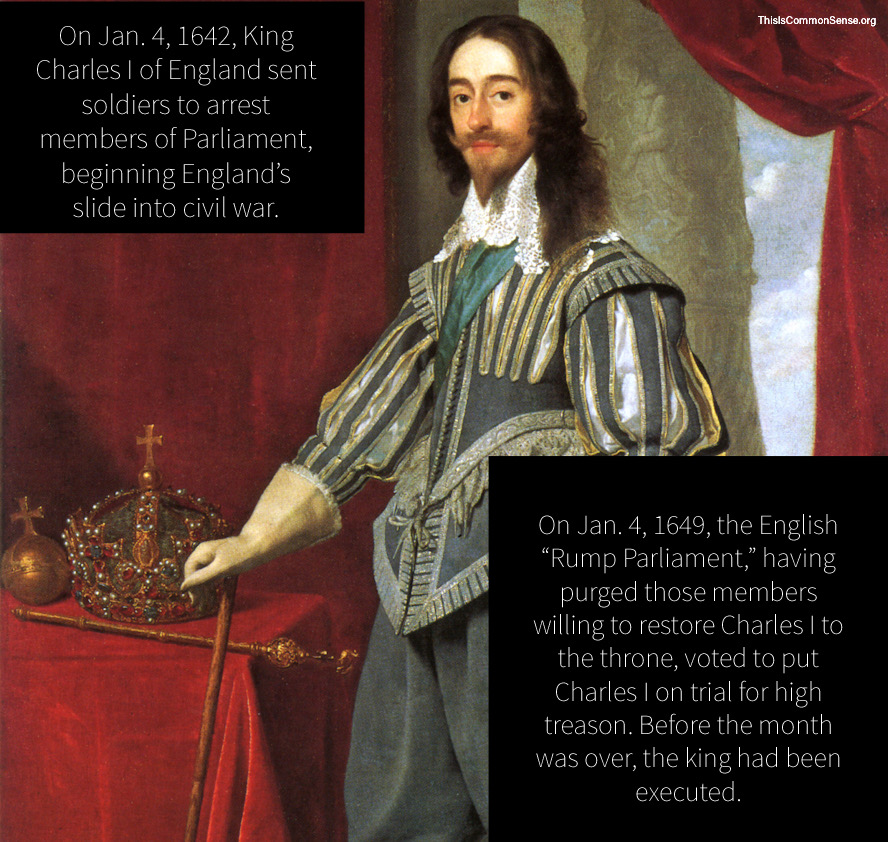

On Jan. 4, 1642, King Charles I of England sent soldiers to arrest members of Parliament, beginning England’s slide into civil war.

On Jan. 4, 1649, the English “Rump Parliament,” having purged those members willing to restore Charles I to the throne, voted to put Charles I on trial for high treason. Before the month was over, the king had been executed.