On September 29, 1789, the first Congress of the United States under the new Constitution adjourned.

On the same date in 1881, economist Ludwig von Mises was born in Lemberg, Galicia, of the Austria-Hungary Empire (now Lviv, Ukraine).

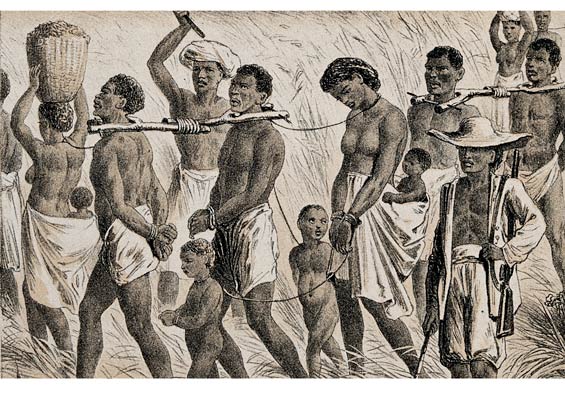

California’s commission on reparations — covered by Paul Jacob here in the past — recommended a huge reparations bill. But of course the State cannot afford it. So Governor Newsome made some hoopla over the issue of slavery, intoning the least sincere apology in recent history. “As part of a California reparations package, Gov. Newsom signs a bill to officially apologize for slavery,” explains CalMatters. “But he vetoed others sought by reparations supporters.”

“This signing event marks a significant milestone in California’s ongoing efforts to promote healing and advance justice,” explains a document from the governor’s office. “The legislation includes critical measures that tackle a wide range of issues affecting Black Californians, from criminal justice reforms to civil rights and education.”

But a less deceptive appraisal can be found from Scott Adams:

“To be an American,” it has been declared, “is to be a radical.” That statement needs qualification. Intellectually the American is inclined to radical views; he is willing to push certain social theories very far; he will found a new religion, a new philosophy, a new socialistic community, at the slightest notice or provocation; but he has at bottom a fund of moral and political conservatism. Thomas Jefferson, one of the greatest of our radical idealists, had a good deal of the English squire in him after all. Jeffersonianism endures, not merely because it is a radical theory of human nature, but because it expresses certain facts of human nature. The American mind looks forward, not back; but in practical details of land, taxes, and governmental machinery we are instinctively cautious of change.

Bliss Perry, The American Mind (1912), p. 77.

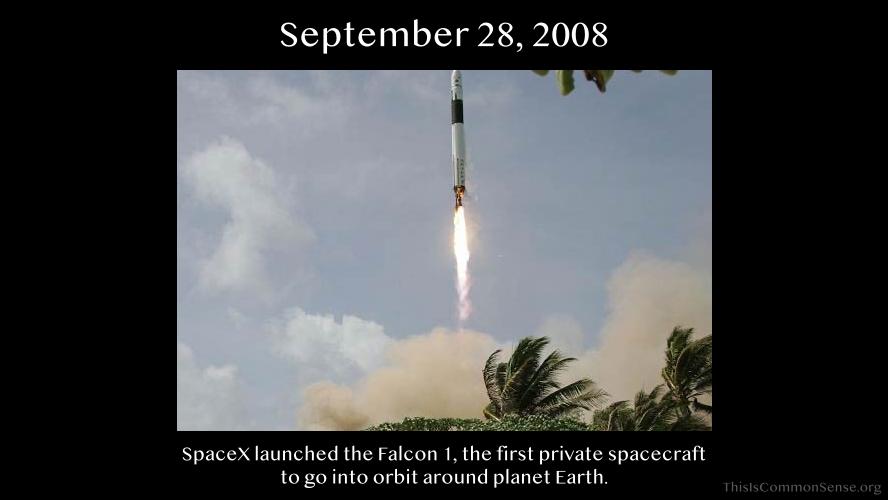

On September 28, 2008, SpaceX launched the Falcon 1, the first private spacecraft to go into orbit around planet Earth.

SpaceX has achieved many records since.

The movie assumes that some cops are bad cops. More specifically, it assumes that bad cops often have arbitrary legal authority to do bad things. In the movie, what gets the ball rolling is the arbitrary authority conferred by America’s civil forfeiture laws.

These laws permit officers to confiscate cash on your person if they merely have a suspicion, or pretend to, that the cash is ill-gotten. They needn’t have evidence that it’s drug money or bank-robbery proceeds.

The suspicion is enough.

And even if you can show that the money was acquired by your own hard work and withdrawn from your bank account in pursuit of a legitimate end — buying a truck, bailing a cousin out of jail (the reason that the protagonist carries cash in Rebel Ridge) — that’s typically not the end of it. It’s rare that the law-empowered thugs who violated your property rights just say “Oops!” and hand your property right back.

J. Justin Wilson of the Institute for Justice observes another realistic portrayal of injustice in the movie, “over-detaining defendants to keep them quiet.” In real life, though, such over-detention may have as much to do with bureaucratic sloth as with malice directed toward a particular prisoner.

The solution, says Wilson, is not revenge, but the kinds of legal reform IJ fights for. The movie, on the other hand, leaned more on revenge.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with PicFinder and Firefly

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

I’ve always wondered whether the theory of the divine right of kings was invented by the kings, to establish their authority over the people, or by the priests, to establish their authority over the kings. It works about as well one way as the other.

H. Beam Piper, “Temple Trouble” (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1951), collected in Paratime (1981) and The Complete Paratime (2001).