Most of us celebrate Labor Day by not working. Labor and celebration being distinct, this is not really as funny as it may sound.

The celebration became federal law in the late 19th century, a time beset by “labor unrest” and “agitation.” At least two major violent incidents at that time can help us understand the origins of our Labor Day, and reduce the current collective blood pressure.

The date of the first was May 4, 1886, a labor demonstration at Haymarket Square in Chicago that went very bad. This Haymarket Affair is one of those handful of stories in our high school history books we tend to remember, involving bombs, deaths, anarchists, hasty prosecution, hangings, pardons, and much more. People still argue about who is to blame. What we don’t argue with is the aftermath: the Second International of communist and socialist parties chose, in 1889, the ancient celebratory day of May 1 to commemorate the Haymarket riot as “International Workers’ Day.”

It has come to be known as “Labor Day” in some countries.

But other, less radical labor activists had already pushed a Labor Day for their cities and states before Haymarket, and they had chosen early September as the proper time for a celebration of “the working man.” A majority of states had enacted early September labor holidays by 1894.

In June of 1894, Congress passed legislation making the first Monday of September “Labor’s Holiday.”

President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law mere days after the Pullman Strike ended — with a not quite universal judgment that he had mishandled it. Cleveland’s intervention in the strike led to a higher body count and more property damage than the Haymarket riot. That being said, it does not appear to have moved President Cleveland as much as you might think — he did not spearhead the Labor Holiday legislation, and his signature is not as important as it may seem, since congressional support was high enough to override any veto.

Associated then with activism to increase the economic and legal power of unions, to this day the official Labor Day in September serves as an alternative to the more radical celebrations in May. But both seem antiquated, now. Our alleged “radicals” today have shifted their focus from labor remuneration and working conditions to providing to workers and non-workers alike free stuff.

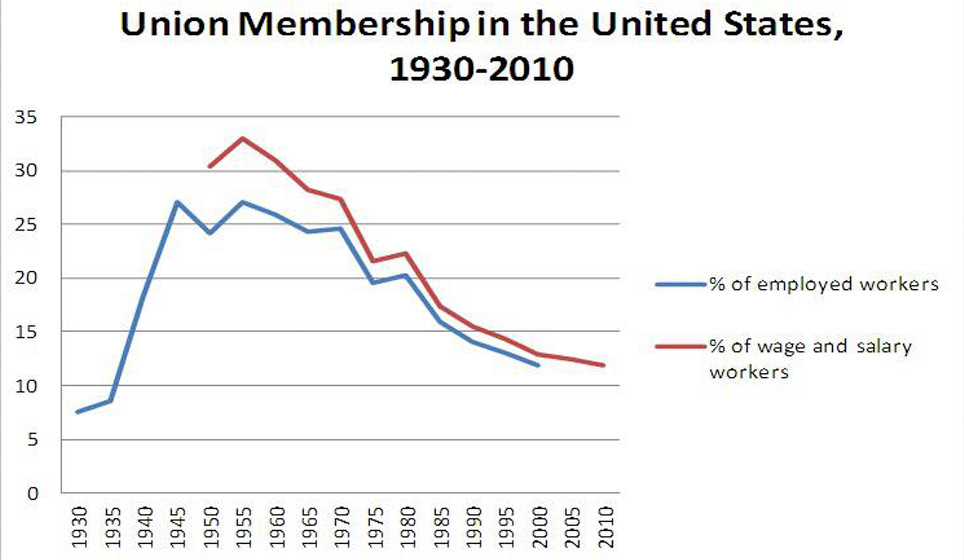

And union participation in America, which waxed up until about the time I was born, has waned since. Only the government worker segment is heavily unionized today.

Nowadays, Labor Day has about the same symbolic and political significance as Arbor Day.

The most important lesson may be this: we talk about how divided the country is, politically and culturally. But the level of foment is not nearly as violent as it was when Labor Day became a national holiday.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)