When socialists and woke scolds talk about slavery, you can almost hear the chains and smell the leather of the slaver’s whip — and not always in a good way.

Project 1619 is the New York Times effort to acknowledge 400 years of Africans in America. Thankfully, the project’s page is more coherent and forthright than Matthew Desmond’s New York Times Magazine farrago of August 14, “In order to understand the brutality of American capitalism, you have to start on the plantation.”

Indeed, that piece (like others in the series) is such a tangle that there is no hope to unravel it in this limited space. Just note that Desmond does his darnedest to help the enemies of liberty tie slavery into the idea of free markets, private property, and free association.*

Project 1619, on the other hand, accepts the complexity of slavery in America without being idiotically tendentious. It recognizes that the captured Africans brought to Virginia shores in August 1619 were treated as indentured servants. Unfortunately, unlike the Englishmen arriving under indentured servitude, the first Africans in Virginia lacked explicit contracts. So negotiating their way out was . . . problematic. Still, one African, arriving two years later, was soon freed and became a landowner. And it was he who was awarded another African as a slave for life, in civil court in 1655, marking the real start of chattel slavery in America.

Which is to say, slavery in America was not exclusively a matter of race.**

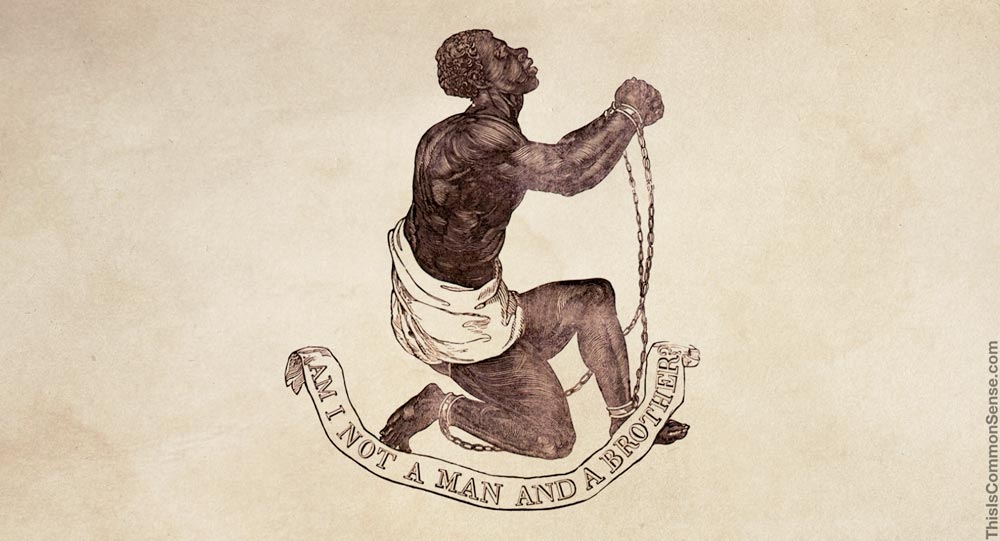

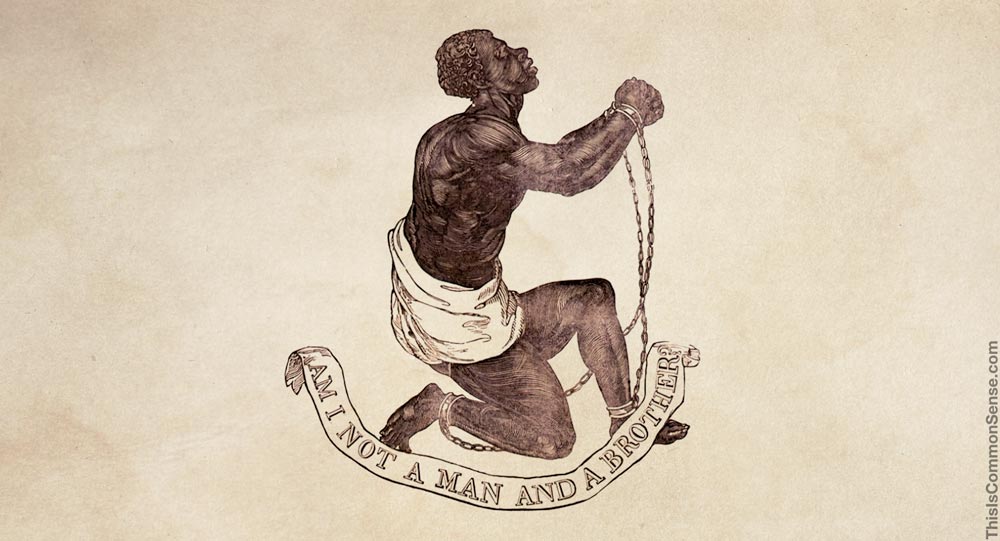

Why is this important? Because slavery is wrong not because racism is wrong (as wrong as that is), but because people have a right to freedom.

Could it be that socialists emphasize racism regarding slavery because they fear that focusing on freedom might scuttle their socialism?

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

* See my discussion of slavery yesterday.

** This becomes clear once you read Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson, or learn how Thomas Jefferson’s wife was related to Sally Hemings

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)