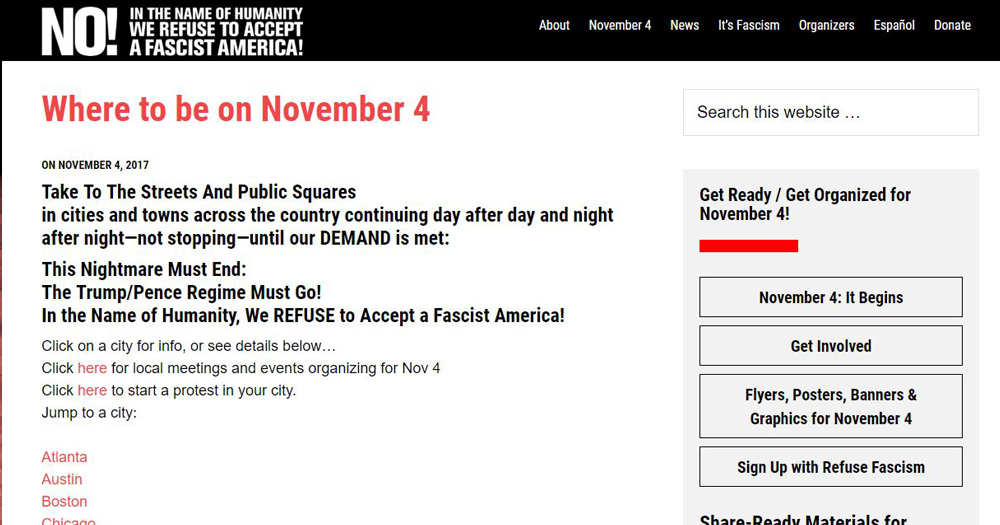

Mass protests have been planned for this Saturday in many major cities across the country. “On November 4, 2017,” says the Refuse Fascism website:

Take To The Streets And Public Squares in cities and towns across the country continuing day after day and night after night — not stopping — until our DEMAND is met:

This Nightmare Must End:

The Trump/Pence Regime Must Go!

In the Name of Humanity, We REFUSE to Accept a Fascist America!

The group took out a full-page ad in the New York Times, repeating all that along with the ominous “Nov 4 • It Begins.”

Now, I am against fascism. You may have noticed that . . . reading between the lines. I’m for limited government, a classical liberal, a modern libertarian. Fascism arose in no small part as a replacement for liberalism, which fascists scorned for not promoting activist government.

And though I’m not gung-ho about President Trump, I do not see much fascism coming from the White House. I challenge tomorrow’s protesters to name five fascist things* the new president has done . . . that the previous president had not also done.

And then, I ask, what practical way could you oppose these putatively fascist things without taking to everybody’s streets until you get your way?

Also, please keep non-violent, as promised. When protesters become rioters, bad things happen — including conjuring up greater authoritarian sentiment from some.

That reaction may not be fascism. But it wouldn’t be good.**

And, on the right: don’t welcome civil war, as some have already done.

Do you want to see blood running in the streets? I sure don’t.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

* Or four? Three? Two? One? Remember, we are talking about new fascism.

** Alas, everything bad in this world is not automatically fascism.