The Economist magazine has announced its “Country of the Year.”

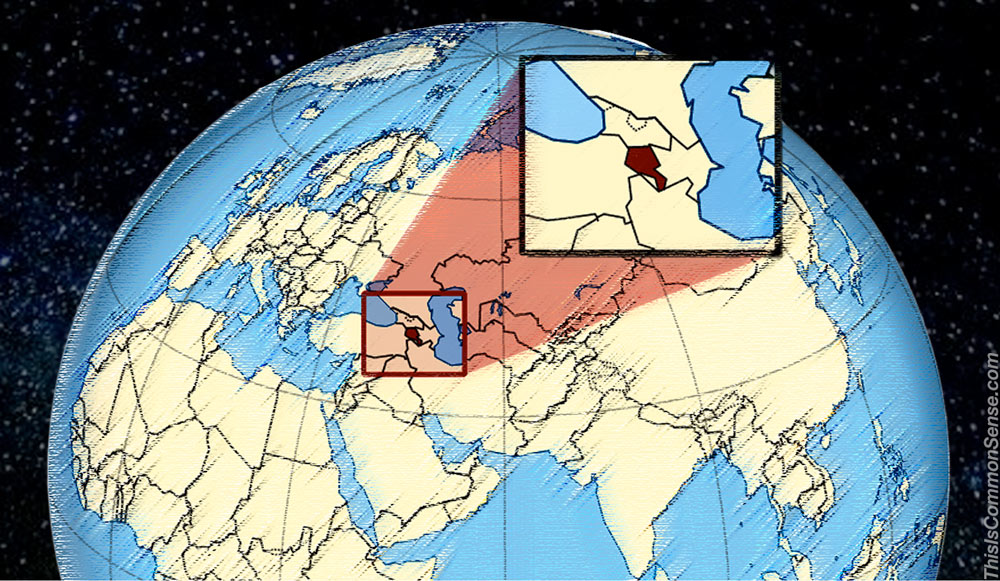

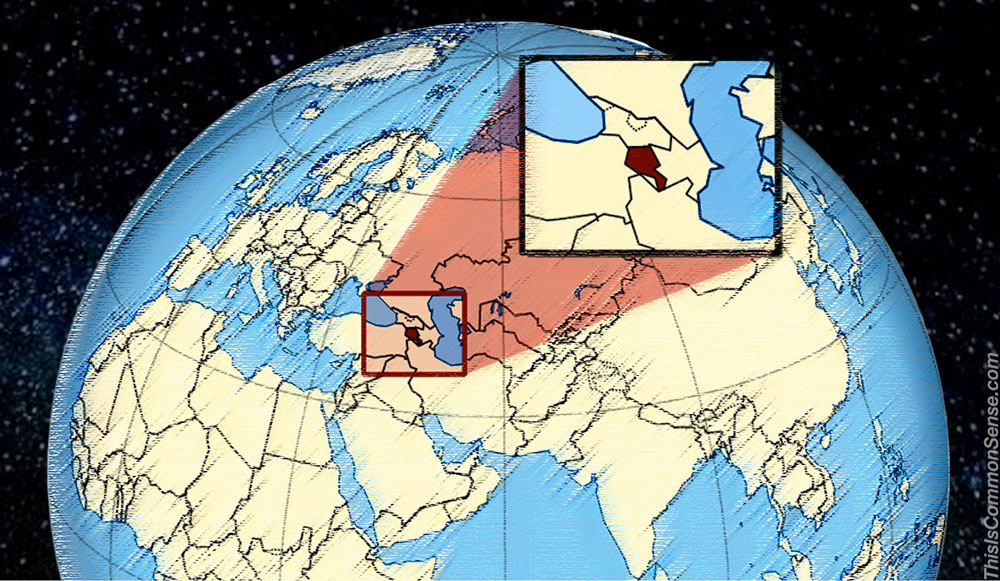

It’s Armenia.

The idea behind the award is to recognize the nation that has “improved the most” during the past year. The honorific implies no rosy assumptions about the future. Obviously, a country can backslide. The Economist’s editors admit that this proved to be the case with prior winners France and Myanmar.

This year, Malaysia and Ethiopia were in the running. Malaysians managed to oust a corrupt prime minister, and the new leader of Ethiopia has sought to encourage freedom of speech and liberalize the economy. But, all things considered, the magazine regards the advances in these countries to be too contradictory or uncertain to merit the Most Improved designation.

Progress seems more definitive in Armenia, where former President Serzh Sargsyan did his darnedest to escape presidential term limits — as is attempted by so many heads of state around the world.

Sometimes the power-grabbers succeed and sometimes they don’t. But everywhere, most voters oppose such shenanigans. They know how easy it is for an incumbent to shove his way to perpetual power no matter how unhappy they may be with him. Citizens know the value of term limits.

Armenia’s good news is that Sargysan’s attack on term limits failed — dramatically. He resigned after massive demonstrations. An opposition figure, Nikol Pashinyan, won power “on a wave of revulsion against corruption and incompetence.… A Putinesque potentate was rejected.”

Just what the world needs to see — a lot more often.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

See recent popular posts

The charge of unnecessariness is surely false when we’re talking about customers who do want the most cutting-edge technology and can put it to good use. But it’s false in a broader perspective too — unless we suppose that all advances in human civilization beyond the level of the hut and the bearskin are “largely unnecessary” to human survival and well-being.

The charge of unnecessariness is surely false when we’re talking about customers who do want the most cutting-edge technology and can put it to good use. But it’s false in a broader perspective too — unless we suppose that all advances in human civilization beyond the level of the hut and the bearskin are “largely unnecessary” to human survival and well-being.