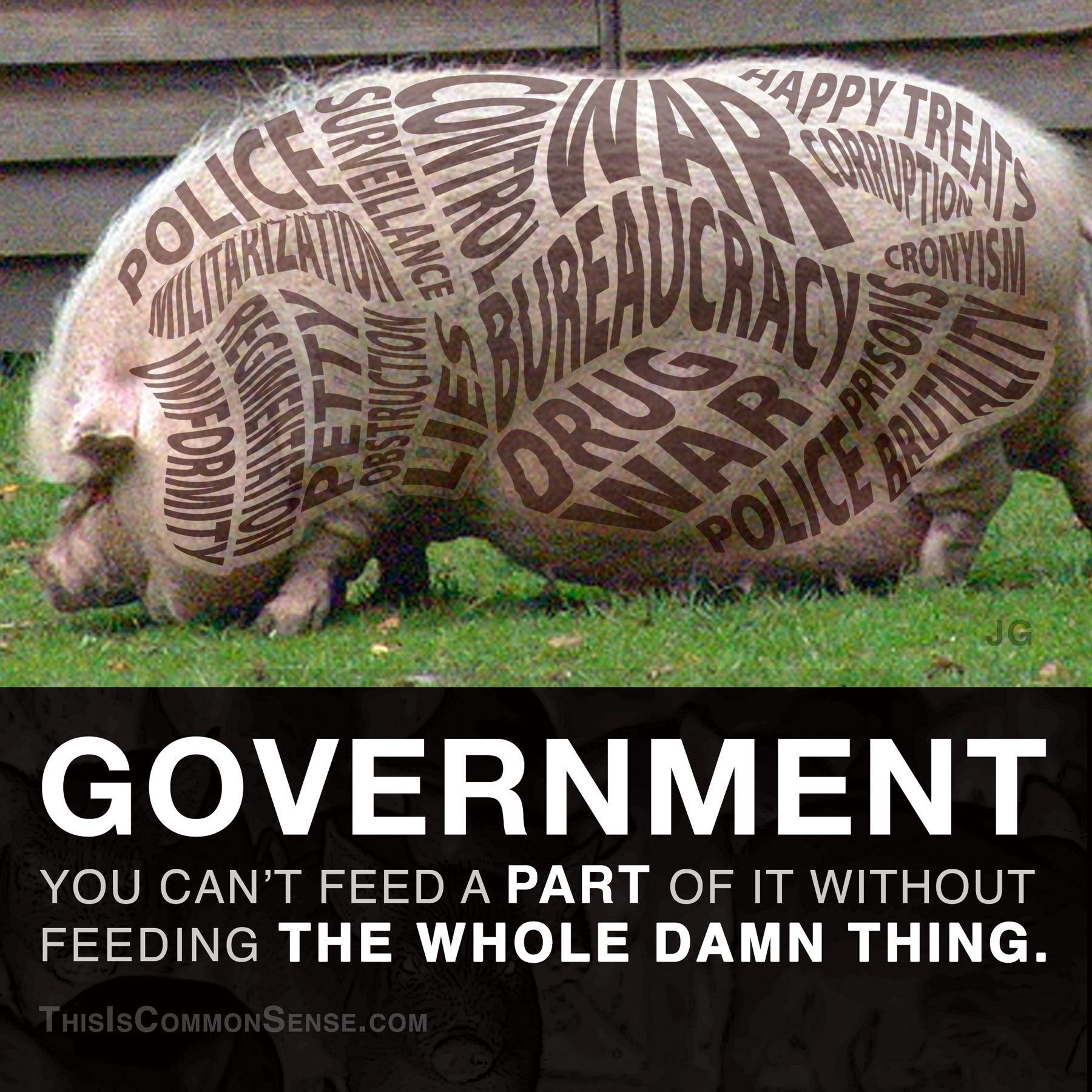

You can’t feed a part of it without feeding the whole damn thing.

Click below for a high resolution version of this image:

The fight against government theft of private property, through “civil forfeiture,” just got a little harder.

There’s a new technology available: ERAD card scanners.

And the Oklahoma City Police Department’s joint interdiction team has them, and can use the scanners to take money from you without your consent.

What money, in particular? The money you have stored in pre-paid debit cards.

ERAD stands for Electronic Recovery and Access to Data, and the ERAD Group, Inc., stands to make a lot of cash from the technology. Police around the country want to be able to take the funds secured in debit cards. It’s the latest thing in the war against the war against the War on Drugs.

Drug traffickers, we’re told, hide dozens of such cards in vehicles transporting drugs.

It’s not enough that police can, in the course of investigating a crime — without conviction, mind you; indeed, without charges being filed — confiscate the cards themselves.

The police also want to be able to siphon the money out of those cards.

Which leads to corruption. Which is already rife in civil forfeiture usage, as a recent Oklahoma state audit found — missing money, misused funds, that sort of thing.

The cavalier way in which government officials defend expropriation by ERAD scanners is chilling. In an Oklahoma Watch article, reporter Clifford Adcock relates the official explanation: “These cards are cash, not bank accounts.… Individuals do not have privacy rights with magnetic stripe cards.” Why not? Because the information on the strip “literally has no purpose other than to be provided to others to read.”

That’s so open to logical criticism you could drive a confiscated truck fleet through it.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

The Institute for Justice’s new report, Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture, details a “big and growing problem” that “threatens basic rights to property and due process.”

Through both criminal and civil forfeiture laws, governments can seize property used in — or the proceeds of — a crime. Criminal forfeiture requires that a person be charged and convicted of a crime to transfer title to government. Civil forfeiture, on the other hand, allows governments to take people’s stuff without being convicted — or even charged — with a crime.

No surprise that 87 percent of asset forfeiture is now civil, only 13 percent criminal. And governments are grabbing more and more. The federal financial take has grown ten-fold since 2001.

“Every year,” IJ’s researchers document, “police and prosecutors across the United States take hundreds of millions of dollars in cash, cars, homes and other property — regardless of the owners’ guilt or innocence.” Then, the innocent victim must sue the government to have his or her stuff returned.

Incentive to steal? “In most places, cash and property taken boost the budgets of the very police agencies and prosecutor’s offices that took it,” an accompanying IJ video explains.

IJ’s report concludes that, “Short of ending civil forfeiture altogether, at least five reforms can increase protections for property owners and improve transparency.” Those five reforms are improvements, sure, but let’s end civil forfeiture completely.

It’s the principle!

Two principles, actually.

Civil forfeiture laws pretend law enforcement is taking action against our property, and that our property has no rights. But what about our property rights!

We’re innocent until proven guilty, too … and so is our stuff.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

and the subsequent two-month Montgomery County (Maryland) Child Protective Services investigation, which found the parents “responsible” for “unsubstantiated child neglect.”

Left unanswered? Whether parents “may” let their kids walk somewhere without supervision.

There’s no law, of course, against children walking in public without parents. But the “swarms of Officers” employed “to harass our people” aren’t limited by trifling things like laws.

This Kafkaesque episode reminds me of my experiences with campaign finance agencies.

In both cases, agencies rely upon meritless complaints to investigate, intimidate and impoverish people without any law being broken. All that’s required? An unelected bureaucrat’s arbitrary decision.

Take Lois Lerner. She ran the IRS division targeting conservative groups. Remember her allegedly lost emails? Irretrievable! Until someone actually looked for them.

Before violating people’s rights at the IRS, Lerner did so heading the Enforcement Division of the Federal Election Commission (FEC). A recent George Will column detailed her threats and very public and politically damaging harassment of Al Salvi, the Illinois Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate. Sure, he was fully acquitted in federal court … after his defeat.

Using a spurious complaint by former Rep. Mike Synar (D‑Okla.), Lerner launched a political persecution against U.S. Term Limits, costing us nearly $100,000 in legal fees and much more in dislocated time and manpower.

Finding no evidence — there was none to find — the FEC finally closed the matter. But agency officials still issued a news release proclaiming that they believed we had violated the law.

An Oklahoma newspaper headline read, roughly, “National Term Limits Group Broke Law, Says FEC.”

Talk about “unsubstantiated.”

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.