Times too tough for much thanksgiving? Some of my readers, surely, are feeling the bracing effects (to put it mildly) of a severe economic slump — a so-called “recession” that I’ve been calling, more simply (and I think more honestly) a “depression” — and all I can say is I have some glimmering of such troubles. Things could definitely be better.

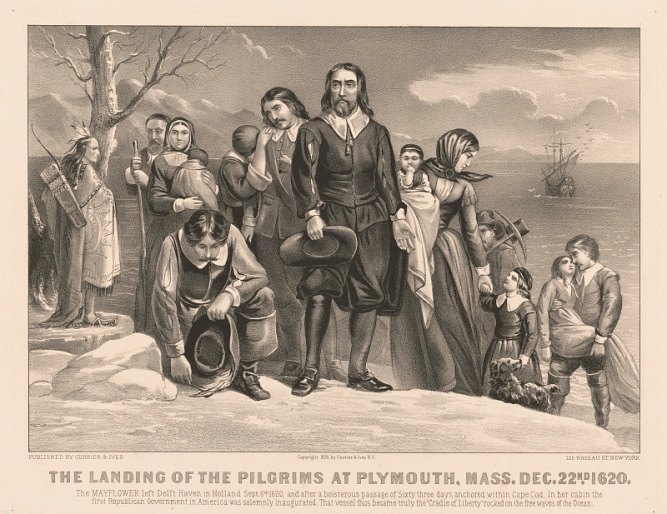

But at Thanksgiving, it might do us good to consult William Bradford’s account of the History of “Plimoth Plantation,” a document that recounts how his fellow Pilgrim settlers established, endured, barely survived, recovered, and eventually thrived in Massachusetts.

By the spring of 1623 — a little over three years after first settlement in Plymouth — things were going badly. Bradford writes of the tragic situation:

[M]any sould away their cloathes and bed coverings; others (so base were they) became servants to [the] Indeans, and would cutt them woode & fetch them water, for a cap full of corne; others fell to plaine stealing, both night & day, from [the] Indeans, of which they greevosly complained. In [the] end, they came to that misery, that some starved & dyed with could & hunger.

The problem? The colony had been engaging in something very like communism.

The experience that was had in this comone course and condition, tried sundrie years, and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanitie of that conceite of Platos & other ancients, applauded by some of later times; — that [the] taking away of propertie, and bringing in comunitie into a comone wealth, would make them happy and florishing; as if they were wiser then God.

Bradford relates the consequences of common property:

For this comunitie (so farr as it was) was found to breed much confusion & discontent, and retard much imploymet that would have been to their benefite and comforte. For [the] yong-men that were most able and fitte for labour & service did repine that they should spend their time & streingth to worke for other mens wives and children, with out any recompence. The strong, or man of parts, had no more in devission of victails & cloaths, then he that was weake and not able to doe a quarter [the] other could; this was thought injuestice. The aged and graver men to be ranked and equalised in labours, and victails, cloaths, &c., with [the] meaner & yonger sorte, thought it some indignite & disrespect unto them. And for mens wives to be commanded to doe servise for other men, as dresing their meate, washing their cloaths, &c., they deemd it a kind of slaverie, neither could many husbands well brooke it.

Yes, the s‑word: Slavery. Common property was mutual slavery.

The solution? The plan for society that Bradford attributed to God. He brooked no pleading that common property didn’t work because of corruption, sin. As he put it, “seeing all men have this corruption in them, God in his wisdome saw another course fiter for them.” The course? I’ll use a word of coined by Robert Poole, one of the founders of Reason magazine: Privatization.

Basically, what the Pilgrims privatized was land, and the fruits thereof, assigning to

every family a parcell of land, according to the proportion of their number for that end, only for present use (but made no devission for inheritance), and ranged all boys & youth under some familie. This had very good success; for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corne was planted then other waise would have bene by any means [the] Govror any other could use, and saved him a great deall of trouble, and gave farr better contente. The women now wente willingly into [the] feild, and tooke their litle-ons with them to set corne, which before would aledg weaknes, and inabilitie; whom to have compelled would have bene thought great tiranie and oppression.

Thus began the years of bounty in Massachusetts. There’s much more in Bradford’s account worth reading, including the increasingly tragic relations with the native Americans. And, indeed, one learns from reading such first-hand accounts how imperfect a creature is man.

But it is obvious that some systems of property and governance work better than others, and, on the day that our government has set forth as a day of Thanksgiving, it is worth being thankful for living in a land that has upheld — to at least some degree — the system of private property that America’s Pilgrim’s learned to see as God’s “fitter course” for corruptible man.

Times may be tough today. On the bright side, they’ve been tougher. One reason for the progress we have seen — even as we endure a major setback, and perhaps a bigger one to come, as the international financial system implodes — is the system of private property that underlies our personal and economic liberties.

Let’s hope we can recover the best in this tradition.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

6 replies on “Plymouth’s Great Reform”

What the good governor was so quick to call corruption is the built in survival instinct, ie to make sure to look of for one’s own needs first, else you will be in no position to look for the needs of others. Any entity that does not have self-preservation as it’s first obgective will come to not exist. And that is what is looked at as corrupt? It is only corrupt for people who hold no value of themselves or their species.

Paul, the problem is that Governor Winthrop hadn’t read his Bible:

I refer, of course, to the Book of Acts, 4:32 — 5:11, Ananias and Sephira. NewLiving translation.

1. There is no doubt that they are practicing the economic system of communism:“All the believers were of one heart and mind, and they felt that what they owned was not their own; they shared everything they had…There was no poverty among them, because people who owned land or houses sold them, and brought the money to the apostles to give to others in need.” From each according to his means, to each according to his need — Marx would have been proud to call them brother.

2. They had as close to an incorruptible body of rulers as possible, who were proving their uprightness with miracles every day.

3. And they had pretty close to the ultimate Auditor; when Ananais and Sephira try to cheat the system, Peter knows about it instantly, and the punishment is swift and sure: the cheaters are struck dead on the spot.

And yet there were still cheaters, the apostles couldn’t hold it together for very long, and none of the other churches outside Jerusalem seem to have even tried it. If the 12 Apostles backed up by God couldn’t make communism work, how in the h*ll would any lesser mortals have a shot??

This site should be called “The Commoner.”

@ SDN — I though about the same scripture. The only way it works is if everyone is “like minded”. As soon as the “like mindedness” leaves utter disaster follows.

In other words; when the lazy decide it is time to kick back and live off the others it fails. Oh wait, they are no longer “like minded”.

The Good Book also says (paraphrased) “if you don’t work, you don’t eat”. That makes sense.

Acts says nothing about communism or socialism; the followers of the Way were not REQUIRED to give their property to the common purse. Communism REQUIRES that. That’s what the problem was in Plimoth plantation also. It’s not the sharing that makes it communist or socialist; it’s the coercion. The whole point to Peter’s remarks to Ananias was that he could have contributed whatever he wanted; he did not have to claim he gave all the money. That’s why the passage specifically says they kept back part of what they got for the sale of the property. They wanted to be thought great and generous. Maybe they believed people would think more highly of them if the said they had given all the money like Barnabas did in the end of the previous chapter. They found out that God is not mocked– and He still isn’t despite the attitudes of much of today’s culture.

The usual telling of the story leaves out that this proto-communism was not proposed out of religious devotion, but more of the backers adopting a strategy the imagined would get them their investment back as quickly as possible, ideally with a surplus.

They thought the “private greed” of the settlers would compete with their growing cash crops for the backers. Backers did not realize that, as history shows, this was unworkable.

Ferdinand Marcos must have had his own version of Marx’s motto.

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his need, and everything left over to me”

His effort was more successful than the Plymouth backers’ partly because he left an illusion of private property. Massive US foreign aid didn’t hurt, either, some calculations have him as pocketing every cent.