Blessed is the man who, having nothing to say, abstains from giving us wordy evidence of the fact.

George Eliot, the nom de plume of Mary Ann Evans (1819 – 1880), Impressions of Theophrastus Such, Ch. 4 (1879).

George Eliot

Blessed is the man who, having nothing to say, abstains from giving us wordy evidence of the fact.

George Eliot, the nom de plume of Mary Ann Evans (1819 – 1880), Impressions of Theophrastus Such, Ch. 4 (1879).

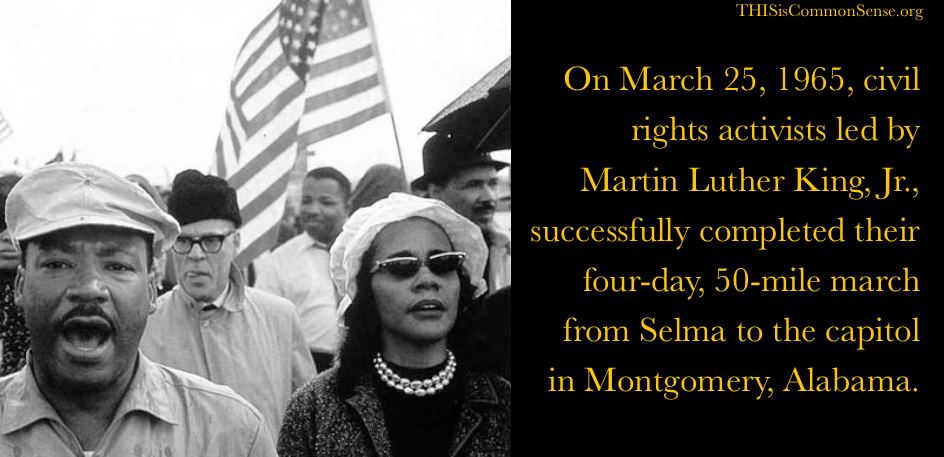

On March 25, 1965, civil rights activists led by Martin Luther King, Jr., successfully completed their four-day, 50-mile march from Selma to the capitol in Montgomery, Alabama.

But what about an agency that exists primarily “to provide luxurious lifestyles for its employees”?

The Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service is one of the agencies getting the ax under the Trump administration, at least until some judge tries to resurrect it.

Nominally, FMCS existed to serve as a voluntary mediator between unions and businesses. But aside from doling out grants to unions and applicants with a tenuous connection to unions, its overriding purpose was to enable employees to splurge on themselves at the expense of taxpayers.

That’s what Luke Rosiak discovered during a year-long investigation.

One FMCS official pretended to take a years-long “business trip” so that taxpayers would foot the bill for his living expenses.

Employees unblocked government credit cards to circumvent protections against abuse, then used them to fund personal expenses. One leased a BMW with the card.

Junkets to resort locations supposedly to drum up interest in the pointless agency were really just a way of enjoying government-funded vacations.

One employee told Rosiak: “Personally, the reason that I’ve stayed is that I just don’t feel like working that hard, plus the location on K Street is great, plus we all have these oversized offices with windows, plus management doesn’t seem to care if we stay out at lunch a long time. Can you blame me?”

Yes, we can.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with Krea and Firefly

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

The people of the United States are entitled to a sound and stable currency and to money recognized as such on every exchange and in every market of the world.

On March 24, 1765, the Kingdom of Great Britain passed the Quartering Act, which required the Thirteen Colonies to house British troops.

On the same date in 1855, slavery was abolished in Venezuela.

“I really thought Trump’s approval might break below 50 today,” Rasmussen Reports pollster Mark Mitchell confessed. “Back up to 51.”

Why?

“He’s doing what he promised to do. Hence the approval.”

Yet it is hard to hear the support from the din of the critics. And some of Trump’s moves do seem reckless, unconstitutional, or at least not well-thought-out.

But significantly unmentioned in most reports is the common-sense revulsion of normal citizens to the riotous vandalism against Tesla owners’ property.

The more Teslas burn, the more electric cars keyed, the more surfaces spray-painted, the higher Trump’s approval rating will likely go. This was the general tenor of Paul Jacob’s commentary from last week.

But as Trump’s popularity bounces back, the Vermont fake socialist’s popularity rises, too:

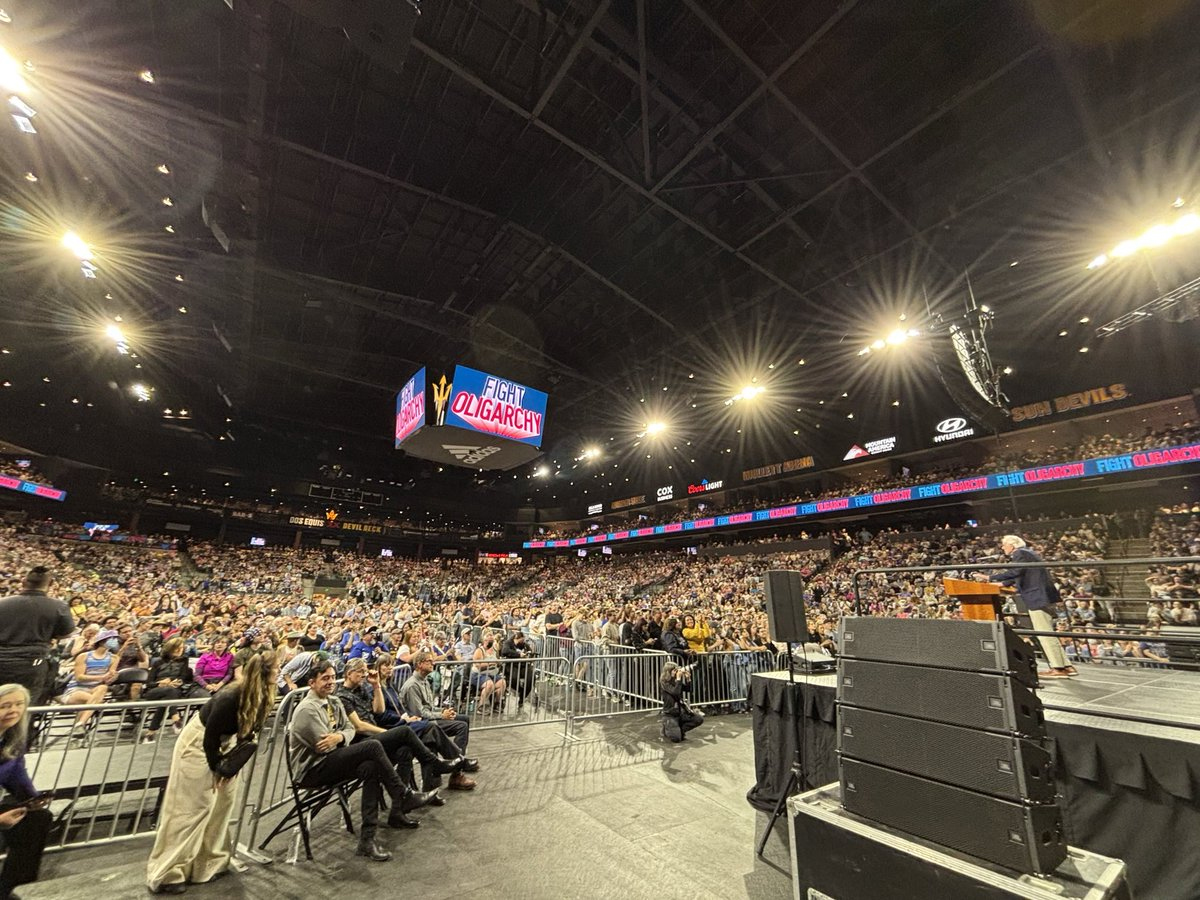

Just to be clear about the moment we’re in:@BernieSanders biggest crowd in Phoenix previously was 11,300 in 2015 when he was running for president.

Tonight, in a non-campaign year, when he is running for nothing, 15,000 Arizonans turned out.

This is a big deal.

Anna Bahr (@anna_bahr), X.com (March 20, 2025).

The question is, will Bernie succeed in revving up crowds while dampening down the wildfire of riot and mayhem?

If he doesn’t do the latter, the opposition to the left will get stronger too, feeding Trump’s popularity. For most people not committed to leftism do in fact disapprove of violence, on the whole — despite the constant fear in the Deep State of “right-wing extremism.”