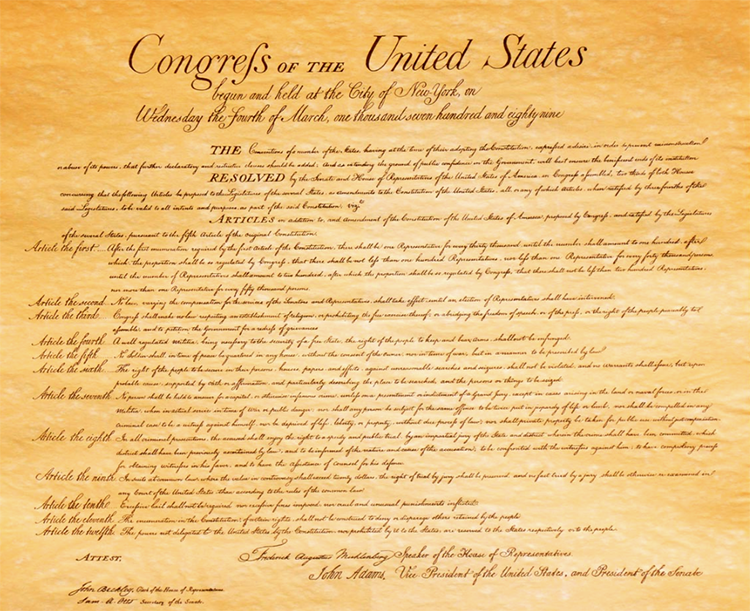

On April 28, 1788, Maryland became the seventh state to ratify the United States Constitution.

Maryland Makes Seven

On April 28, 1788, Maryland became the seventh state to ratify the United States Constitution.

“When this is all over, the NHS England board should resign in their entirety,” Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, quoted an employee of Britain’s National Health Service.

Horton agrees. It’s “a national scandal.”

But now things are looking up.

“[T]he British government asked people to help the National Health Service,” reports The Washington Post, “it called for a ‘volunteer army.’”

“The NHS is ‘rallying the troops’ for the war on coronavirus,” reads the NHS webpage, “with volunteers being called up to help vulnerable people stay safe and well at home.”

The results?

“Within four days, 750,000 people had signed up,” The Post quantified, “three times the original target and four times the size of the British armed forces.”

The newspaper story recounts several endearing tales of people inspired to serve their fellow Brits. And now the website’s sign-up page notes recruiting has been paused — to process the applications.

That’s certainly not the tack taken by New York’s Bill de Blasio. “Mayor de Blasio today called on the federal government to institute an essential draft of all private medical personnel to help in the fight against COVID-19,” informed the city’s website.

Sadly, the mayor wasn’t alone. At Foreign Policy, University of Massachusetts professor Charli Carpenter asked, “But why isn’t compulsory service on the menu of policy options right now?”

Why would a politician and a professor demand to conscript citizens of a free Republic?

Without ever asking for volunteers.

Meanwhile, ABC News notes that “[m]ore than 9,000 retired soldiers have responded to the U.S. Army’s call for retired medical personnel to assist with the response to the novel coronavirus pandemic,” and others are rushing to help.

As free people are known to do.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

See recent popular posts

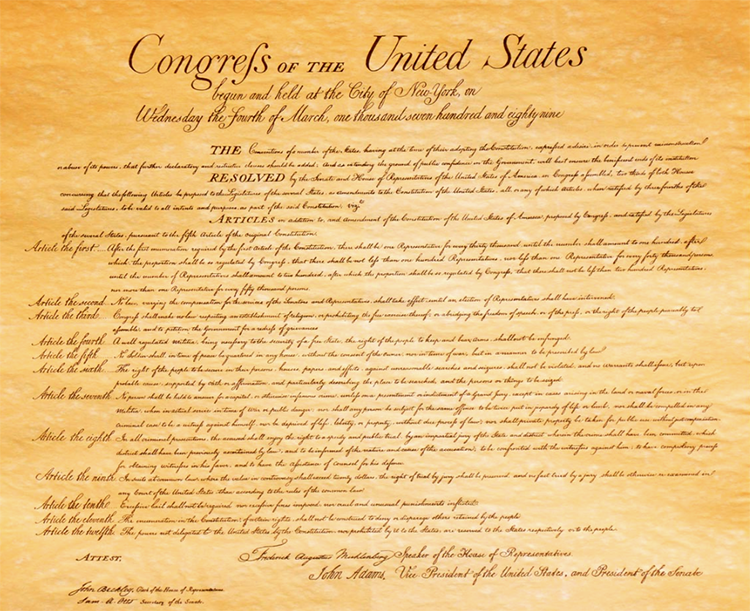

English philosopher, psychologist, sociologist, and political theorist Herbert Spencer was born in Derby, England, on April 27, 1820. Among Spencer’s most famous books are First Principles, Principles of Ethics (chiefly its first part, The Data of Ethics), The Study of Sociology, The Man versus the State, and two editions of Social Statics. Spencer was an evolutionary theorist as well as a religious and political philosopher, and coiner of the phrase “survival of the fittest.” He called the basic principle of a free political order “The Law of Equal Freedom.”

In the previous century, on the same day in 1759, English philosopher and author Mary Wollstonecraft was born. Wollstonecraft married anarchist philosopher William Godwin and the couple begat one daughter, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus. Wollstonecraft herself wrote one infamous and valiant effort in the emancipation of women, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, in 1792.

Paul goes on the record for the week:

On April 26, 1777, Sibyl Ludington, aged 16, rode 40 miles to alert American colonial forces to the approach of the British. Her ride was over twice as long as the more famous Paul Revere’s.

On the same day in 1805, United States Marines captured Derne under the command of First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, an important event in the First Barbary War. In April 26, 1865, Union cavalry troopers cornered John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Lincoln, in Virginia, shooting him to death. There was no interrogation.

China, homeschooling, and more big stories of the week, reviewed in depth by Paul Jacob:

April 25 is celebrated as Freedom Day in Portugal.

The current pandemic panic and crisis, Brian Doherty noted in Reason, “is a harshly vivid example of Americans’ inability to understand, fruitfully communicate with, or show a hint of respect for those seen to be on other side of an ideological line.”

Mr. Doherty, who profiled me in his book Radicals for Capitalism, calls the two major positions “Openers” versus “Closers.”

They do not trust each other, and their respective policy prescriptions — opening up society to normal commerce versus keeping it closed, under lockdown — are poles apart.

Doherty doesn’t mention how we treat experts. Virologists, medical doctors and epidemiologists also form ranks on both sides, and these experts sure seem to be talking past each other, too.

Which seems neither professional nor scientific.

Doherty concludes by asserting that, even after obtaining answers to questions regarding “the disease’s spread, extent, and damage” or coming to an eventual conclusion regarding “the long term damage to life and prosperity the economic shutdown is causing,” we must admit that “human beings of goodwill and intelligence might come to a different value judgment about what policy is best overall.”

Sure. But, looking over the divide as he presents it, I am afraid I see one side — the Openers — concerned about a broad number of possible disasters (economic dislocation and even mass starvation in addition to illness and death) while the other — the Closers — obsessing about fighting a disease about which there remains limited knowledge and little agreement.

The Openers seem a whole lot more open to diverse considerations.

Including the possibility that freedom might result in a better collective response than orders issued by mayors and governors and the president.

Which strikes me as more like Common Sense.

I’m Paul Jacob.

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)

See recent popular posts

On April 24, 1792, the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” was composed by Capt. Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle.

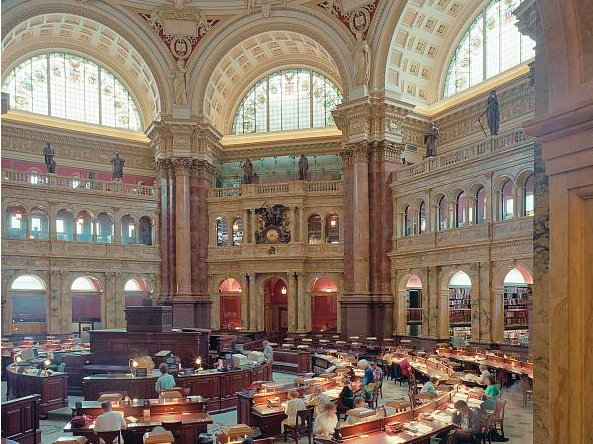

Eight years later to the day, the United States Congress approved a bill establishing the Library of Congress.

Can liberty be born from the bosom of despots? and shall justice be rendered by the hands of piracy and avarice?

Constantin-François de Chassebœuf (1757 – 1820), Comte de Volney, The Ruins; Or, Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires: And The Law of Nature, Chapter II (Thomas Jefferson, translator).