At 5:00 pm today, I’ll close my office door and take a few minutes to quietly reflect upon heroism, honor, courage and fealty to truth.

I’ll grieve for those who’ve suffered the sometimes tragic consequences of correctly answering Patrick Henry’s historic question: “Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?”

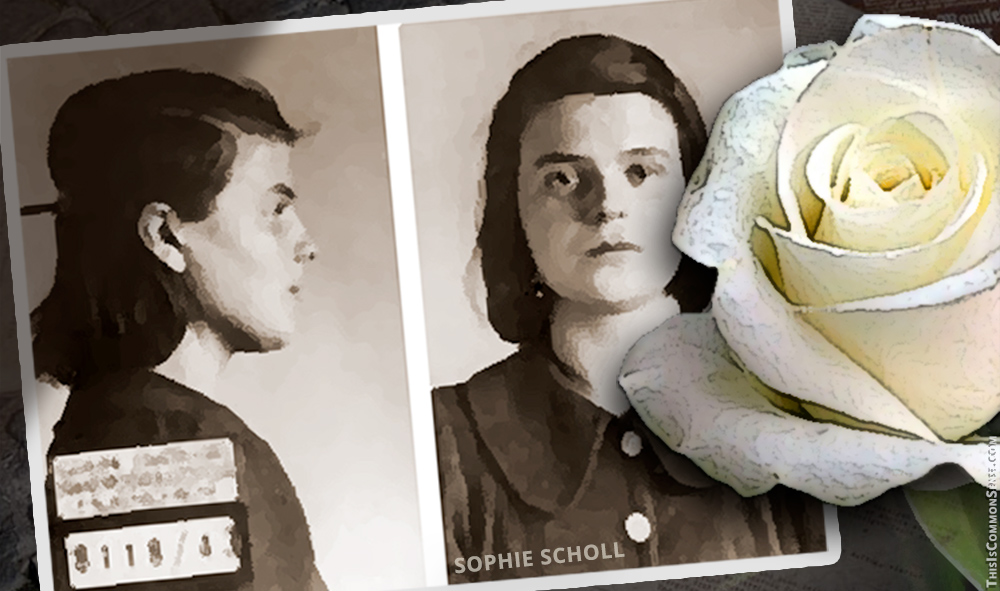

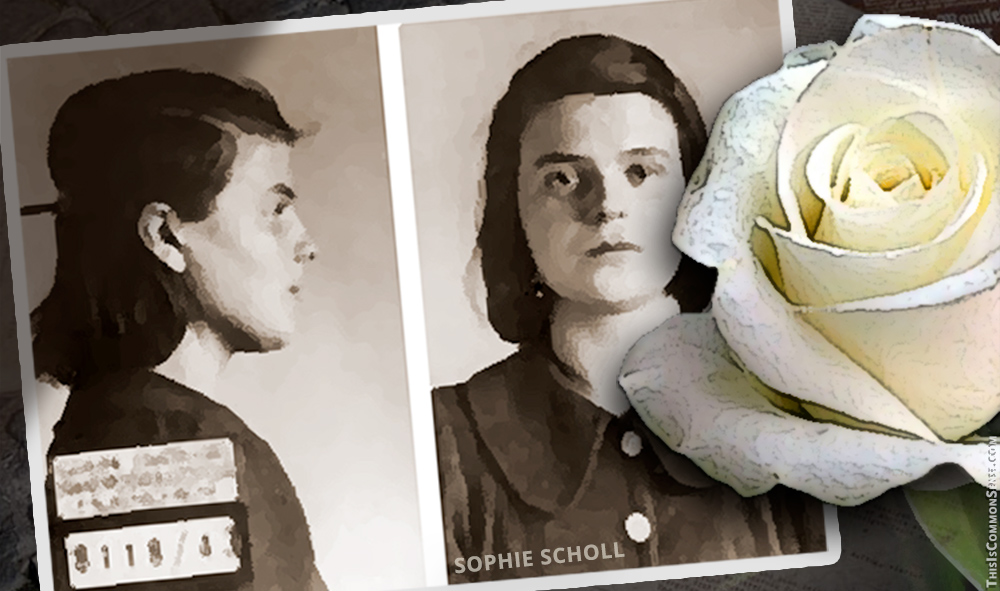

Sixty-nine years ago today, at 5:00 pm Munich time, three German youths — Sophie Scholl, her brother, Hans, and their friend Christoph Probst — were put to death by the Nazis. They were decapitated, guillotined, within hours of being found guilty in a show trial.

Their crime? Standing up against the most evil crime imaginable.

The charge was treason — treason committed courageously against the Third Reich. Richard Hanser’s 1979 book on the subject is aptly titled, A Noble Treason: The Revolt of the Munich Students Against Hitler. Sadly, it’s now out of print, but thankfully still available.

The Scholls had a history of standing up to the Nazis. Hans was arrested in 1937 for involvement in the German Youth Movement, an unapproved group. In 1942, Hans and Sophie’s father, Robert, the former mayor of Forchtenberg, was imprisoned for several months for telling his secretary, “This Hitler is God’s scourge on mankind.”

So, perhaps it was no surprise that the Scholls helped organize a group known as The White Rose, comprised mainly of students at the University of Munich. These young people saw Hitler and the Nazis as pure, unadulterated evil — as a threat to all that is good and true.

They were convinced that most Germans felt the same way. But they knew folks were too afraid to speak up, to stand up, and to resist the evil in front of them. After all, the price would almost assuredly be death, and life is mighty dear.

The White Rose dissidents found the courage to put the “lovely intangibles” of justice and decency and truth ahead of safety and even life itself. In addition to painting “Down with Hitler” graffiti on buildings in Munich, the group produced six pamphlets from June 1942 until February 1943 urging Germans to rise up against Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. The leaflets were distributed to students at the University, where they caused quite a stir, as well as throughout Germany — some even making their way to occupied countries.

The White Rose leaflets and anti-Nazi graffiti unnerved the Gestapo. After all, this brazen public rebuke to their authority might inspire others to rise up in opposition. In a state otherwise tormented into silence, the totalitarians were frustrated in their inability to find and crush this resistance.

Then, on February 18, 1943, Hans and Sophie were caught distributing leaflets at the University, and promptly arrested. Hans was only 24 years old, Sophie just 21. Hans was carrying a note from Christoph, a 22-year old medical student, who was quickly arrested as well.

Afraid of public sympathy for these young people, the Nazi state moved quickly, putting the three on trial just four days later, on February 22. Roland Freisler, chief justice of the People’s Court of the Greater German Reich, came in to preside, and to lambast and scream at the three “traitors.” At one point, the judge asked how the three could turn against the country that reared them. Sophie stoically responded, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare to express themselves as we did.”

The judge sentenced all three to death. Hours later, after the Scholls’ parents had visited, but before Christoph Probst’s wife, who was in the hospital having their third child, could see her husband one last time, the three were taken to the guillotine. Hans Scholl’s last words were: “Es lebe die Freiheit!” (Long live freedom!).

The Scholls and Probst were not the last of The White Rose activists to die for speaking truth to tyranny. Co-conspirators Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf were put to death later in 1943, as was University of Munich Professor Kurt Huber, in whom the students had confided. Others involved in the effort were sent to prison.

Professor Huber, believing, unlike his young friends, that Germany would still win the war, said at his trial, “We do not want to fritter away our short lives in chains, even if they are golden chains of prosperity and power.”

Today, I’ll think about the Munich students’ revolt against Hitler. And thank them. And thank all those, today and throughout history, who have risked, suffered, or died, because they chose liberty.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.