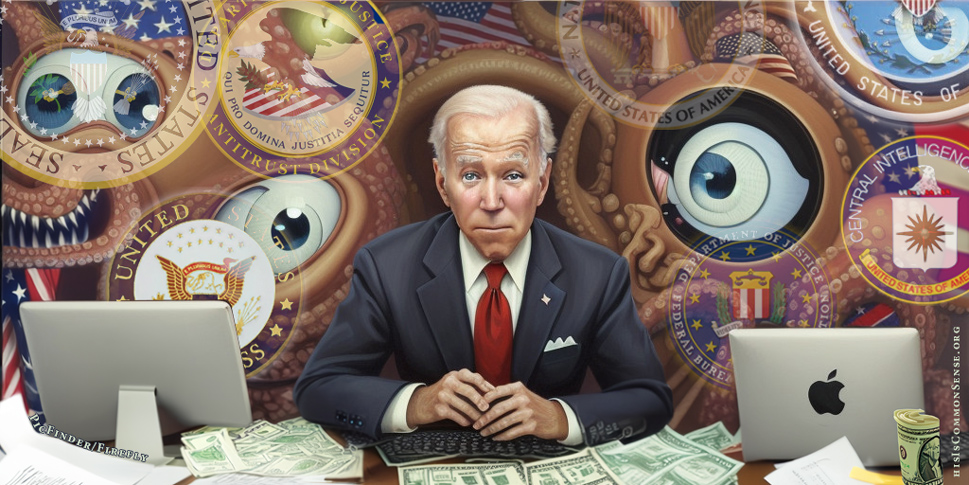

The Biden Administration makes much of its pro-consumer actions. President Sleepy Joe never tires of boasting about how his regulations favor consumers over credit card companies. Considering the massive taxation that his administration supports, however, saving a few bucks on overdraft fees looks a bit absurd in context.

As does the administration’s ramped-up

The federal government has now attacked Apple. On anti-trust grounds. For being a monopoly.

The humor in this was noted by anti-intellectual property theorist Stephan Kinsella, tweeting on X: “‘U.S. Sues Apple, Accusing It of Maintaining an iPhone Monopoly’ We grant you patent and copyright monopoly privileges and you use them to build up a monopoly? How dare you!”

Jeffrey A. Tucker of the Brownstone Institute was less amused, and less concerned with Apple’s reliance upon intellectual property, which he claims is secondary to the company’s useful products: “The very notion that the government is trying to protect consumers in this case is preposterous. Apple is a success not because they are exploitative but because they make products that users like, and they like them so much that they buy

At issue is how Apple products work so well together but not so well with other manufacturers’ products. “The Justice Department calls this anticompetitive even though competing is exactly the source of Apple’s market strength,” insists Tucker.

Maybe it’s really about this principle: the government giveth; the government taketh away: blessed be the name of the Biden.

In full disclosure, I have an iPhone, which I hate, and a Microsoft Surface Book, which I also hate. I’m open to any of their competitors, which I might hate less.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

Illustration created with PicFinder and Firefly

—

See all recent commentary

(simplified and organized)