There used to be comity in Washington, D.C., because there was a system in place that allowed the two vying parties to fleece the public while “justifying” the fleecing. Paul Jacob wrote about this over a decade ago:

[H]ere was the genius of the system: The slight cuts in growth rates allowed left-leaning Democrats to hysterically decry the cruelty of the “cuts” that Reagan was “imposing” — courtesy of the accounting tricks allowed by the post-Nixon Budget Control Act — despite the illusory nature of those cuts.Republican politicians, meanwhile, could go home to boast of those “cuts.”

Meanwhile, deficits ballooned under Ronald Reagan, and Republican voters came to accept deficit financing (growth in debt) as a natural thing, almost good. With the ascension of George W. Bush to the presidency, and a post-Clintonian reaction giving majorities in both houses to Republicans, this trend solidified.

Paul Jacob, “Dumbline Democracy,” Townhall (July 8, 2012).

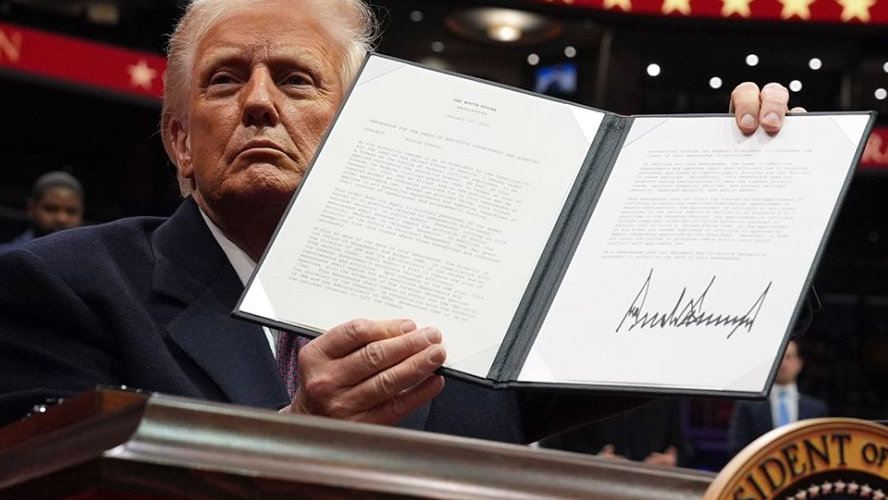

The comity ended as increasing numbers of Americans came to disbelieve in the confidence game the two parties engaged in. This led to the selection by one of the parties of a candidate enough outside the con artists’ guild to upset the out-of-control order. Trump, that is.

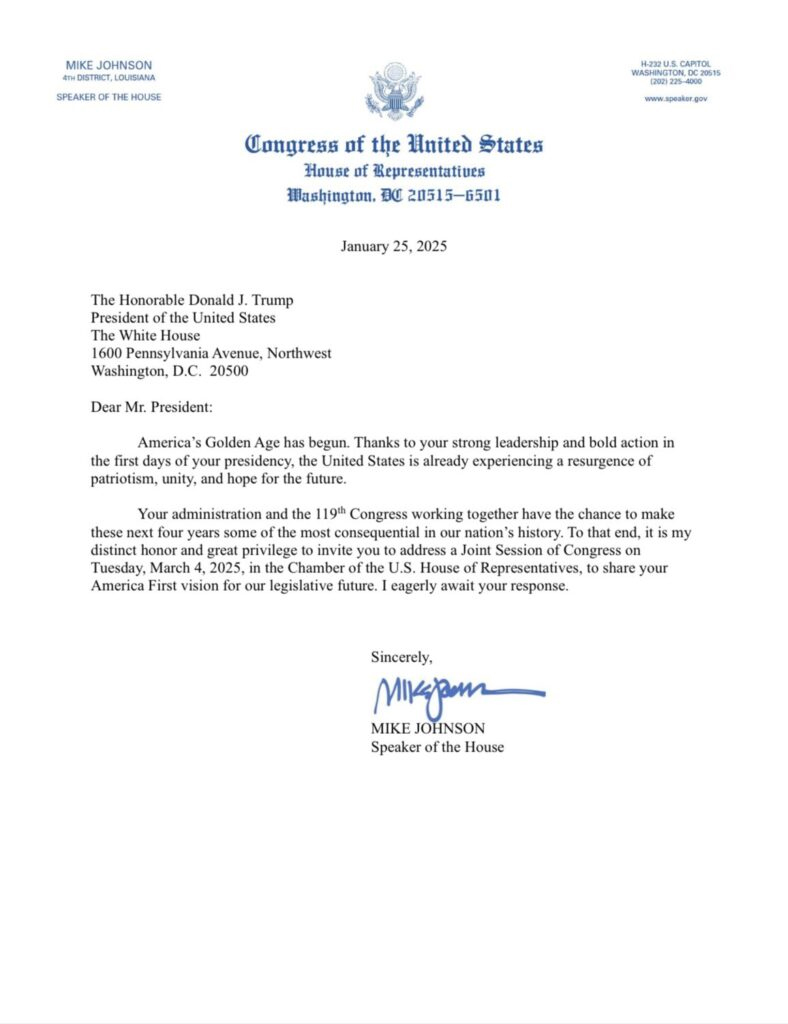

So now that key bit of legislation, the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, is finally under serious targeting:

In a move that could give President Donald Trump more freedom to enact his agenda, Republicans are attempting to repeal a law which ties the hands of presidents who don’t want to spend particular funding appropriated by Congress.

Known as impoundment, the practice of declining to spend funds provided by Congress dates back to President Thomas Jefferson.

Since 1974, however, it has been tempered by the Impoundment Control Act (ICA).

Nathan Worcester, “Republicans Seek to Unleash President’s Power to Not Spend,” The Epoch Times (February 16, 2025).

The constitutionality of impoundment has never reached the Supreme Court. The practice was started by Jefferson, who used it to stop Congress from unconstitutional spending — but because impoundment was not in the Constitution itself, it’s open to obvious challenge, and to the argument that it is an example of executive overreach.

The whole issue comes down to the fact that the Constitution provides inadequate means of the executive to stop Congress from unconstitutional acts, as well as the states to stop the federal government as a whole from the same. The constitutional crises associated with slavery expansion in the mid-century are now endlessly discussed. But current dysfunctional partisan over-spending is at least as serious a problem.

Thankfully, we have an easier marker for a constitutional crisis now:

See also “The Fourteenth Amendment Escape Clause,” July 8, 2011.