In 1984, twenty-seven years ago this very day, three FBI agents pushed their way into my North Little Rock, Arkansas, home and placed me under arrest.

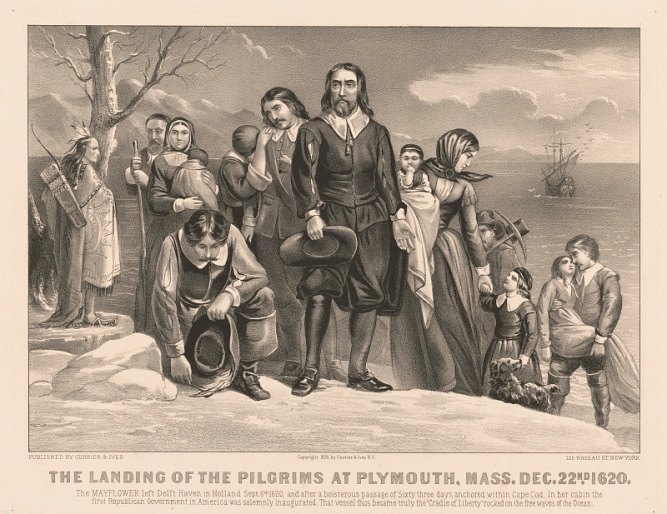

My crime? Violating the Military Selective Service Act — that is, absolutely, positively, publicly refusing to register for the military draft. (I’d have resisted civilian service just as ardently.)

Some folks might call it dodging the draft. But not so — I met the draft head on, and in the great spirit of civil disobedience, I resisted.

Of course, there was no actual draft of young men into the military, simply a bureaucratic and regimented preparation for conscription. Seemed like the optimum time to let Uncle Sam know not to plan on me.

Rest assured, had the country been attacked I’d have been there lickety-split. It was not the military or defending the country to which I objected; it was doing it as a conscript — a slave — rather than as a free man.

I expressed my rationale in detail in several of my writings below, from 27 years ago as well as more recently. But my view was and remains neither radical nor alien, tracking, as it does, with what Ronald Reagan said in 1980: “The draft or draft registration destroys the very values our society is committed to defending.”

As is par for the political course, it was Mr. Reagan’s Justice Department that prosecuted me for continuing to stand up for those “values.” U.S. Rep. Ron Paul, today a presidential candidate, testified on my behalf at trial.

At the trial, the prosecutors freely admitted they had every stitch of personal information the government needed the better to spit me out a draft notice should they decide to conscript young Americans. They lacked only my signature on the form.

But that is what they wanted most: my acquiescence. The law said I must “present myself and submit” to registration. I had not submitted to it; I would not — could not in good conscience do so.

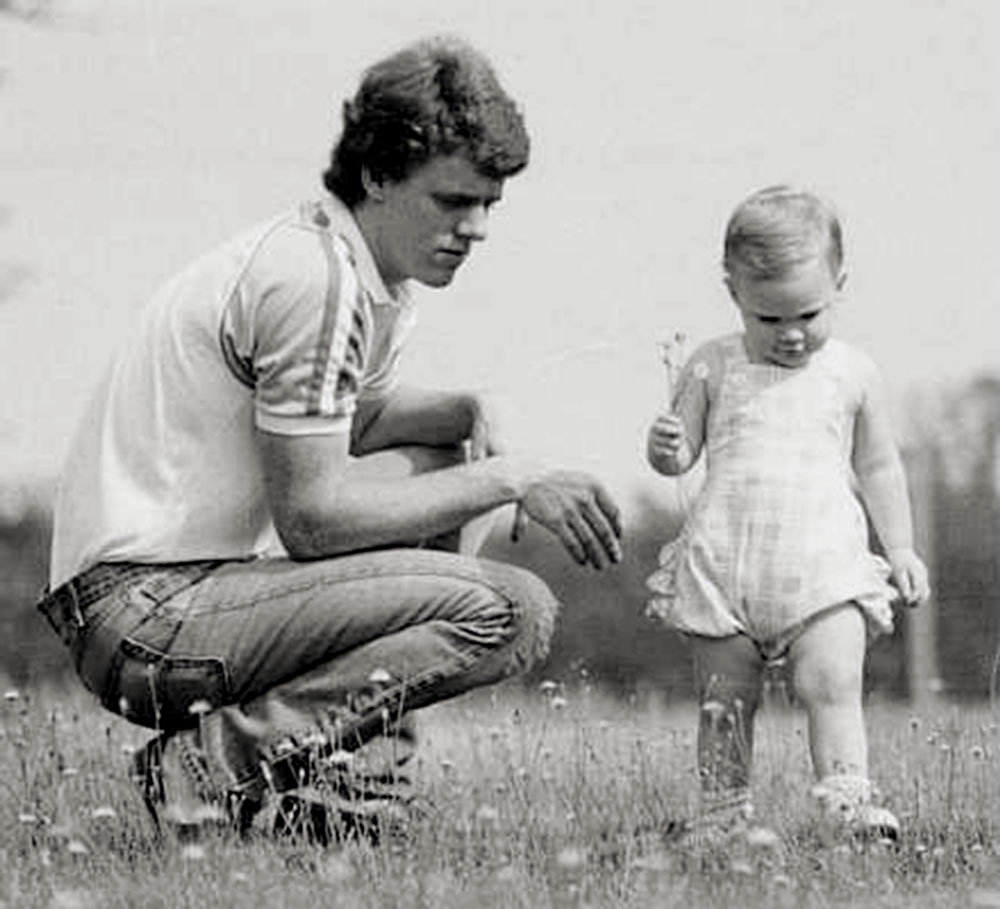

At 24 years of age, with wife and an eight-month old daughter, it was certainly a bit disconcerting to begin my adulthood, my career, as a felon. Moreover, to take that risk simply on the principle of the matter, that conscription is un-American, a totalitarian idea, and not because I was actually threatened with being drafted.

Had I wished not to serve, I could have signed up only to refuse to go when the draft notice arrived … or I could have quietly refused to register, and faced no threat of being prosecuted. But my goal wasn’t to personally escape the draft. It was to prevent the draft from coming back, to prevent the damage the draft does to our freedom and our country by enabling a foreign policy of acting as the world’s policemen.

Some disagree with the politics of my stand. They have a right to their opinion. But I think that what we ask of everyone should be to do what they believe is right. Not to be a silent spectator, but to speak up and, when necessary, to take action.

In the end, I was convicted and served five and a half months in a Federal Correctional Institution. For better or worse, the “correction” didn’t take.

And never for an instant have I regretted doing what I thought was right.

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob.

further reading:

Why I Refuse to Register, 5/17/1985

Draft the Congress and Leave My Kids Alone, 12/28/2003

Americans Gung-Ho to Draft Congress, 1/4/2004