“The subjects of every state,” says Dr. Smith, “ought to contribute [490] towards the support of the government as nearly as possible in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.”

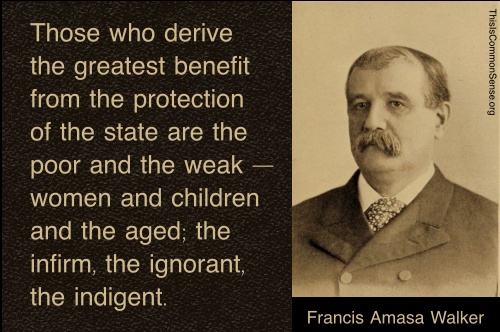

This maxim, though it sounds fairly, will not bear examination. What mean those last words, “under the protection of the state”? They are either irrelevant, or else they mean that the protection enjoyed affords the measure of the duty to contribute. But the doctrine that the members of the community ought to contribute in proportion to the benefits they derive from the protection of the state, or according as the services performed in their behalf cost less or cost more to the state, involves the grossest practical absurdities. Those who derive the greatest benefit from the protection of the state are the poor and the weak — women and children and the aged; the infirm, the ignorant, the indigent.

Even as among the well-to-do and wealthy classes of the community, does the protection enjoyed furnish a measure of the duty to contribute? If so, the richer the subject or citizen is, the less, proportionally, should he pay. A man who buys protection in large quantities should get it at wholesale prices, like the man who buys flour and meat by the car-load. Moreover, it costs the state less to collect a given amount from one taxpayer than from many.

Returning to the maxim of Dr. Smith, I ask, does it put forward ability to contribute, or protection enjoyed, as affording the true basis of taxation? Which? If both, on what principles and by what means are the two to be combined in practice?

Francis Amasa Walker, “The Social Dividend Theory of Taxation,” in Political Economy (Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged: 1888), pp. 489 – 490.

Categories

Francis Amasa Walker

One reply on “Francis Amasa Walker”

“In the textbooks of middle-schools, of high-schools, and of introductory courses in college on civics, on politics, or on economics, there are discussions of various proposed guidelines for taxation, based on ostensible or insinuated theories of justice. One commonly offered theory is that people should be compelled to pay based upon supposed ability; another is that they should be compelled to pay based upon the amount of services that they receive from the state. I’ve yet to see such a discussion in such a textbook that could withstanding much critical examination.

“In any case, these homilies don’t serve to explain how-and-why taxation is effected in the real world, except in-so-far as some of their prescriptions are invoked to argue for a tax of one sort, even as conflicting rationalizations are offered (often by the very same people) to argue for taxes of other sorts. Historically and to the present day, taxation has been fundamentally opportunistic. That which has been taxed is whatever seemed to be most readily taxable. Targets of convenience have been wealth or income that has been thought to be easily tracked and measured, difficult to relocate outside of the jurisdiction, or for the taxation of which there is wide-spread acquiescence if not support within the community. (It is with respect to that last aspect that textbook theories have their real relevance.)”

— “On Deductibility of Local Taxes”, an entry in my ‘blog