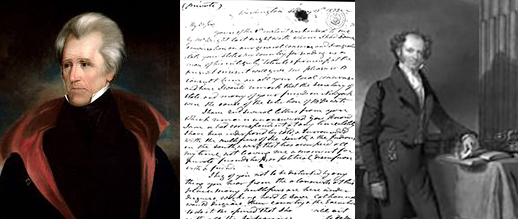

On January 13, 1833, United States President Andrew Jackson (pictured, top left) wrote to Vice President Martin Van Buren (pictured, top right) expressing his opposition to South Carolina’s defiance of federal authority in the Nullification Crisis. Jackson insisted that “the crisis must be now met with firmness” and “the modern doctrine of nullification & succession put down forever.”

South Carolina had blamed protectionist high tariffs for the severity of the economic slump of the time, and Andrew Jackson’s compromise Tariff of 1832 was still too much special-interest “protectionism” for South Carolina, which threatened to nullify the law as unconstitutional. Jackson, a nationalist at heart, had no sympathy for dissidents in the southern states. (The tariffs were designed by northern politicians to encourage the growth of industry. The belief among most economists of that time was that such high “protective” tariffs favored certain businesses at the expense of the general consumer, particularly farmers and agricultural producers.) After the crisis subsided, tariffs were further reduced from the 1832 level, much lower than of 1828’s “Tariff of Abominations,” which had been signed into law by President John Quincy Adams — and written mainly by Martin Van Buren as a way to precipitate the election of Jackson.

Since the somewhat ambiguous end to the Nullification Crisis, the doctrine of state prerogatives — “states’ rights” — has been asserted by opponents of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, proponents of California’s Specific Contract Act of 1863 (which nullified the Legal Tender Act of 1862), opponents of Federal acts prohibiting the sale and possession of marijuana in the first decade of the 21st century, and opponents of implementation of laws and regulations pertaining to firearms from the late 1900s up to 2013. State opposition to ObamaCare has also recently conjured up the issue.

On January 13, 1898, Émile Zola’s J’accuse exposed the Dreyfus affair.

1 reply on “Nullification?”

The US Constitution has never specified who has the power to find an Act unconstitutional. The original failure to do so can be explained by a presumption that dissatified states could seceed. Empowering states unilaterally to effect a decision that an Act were unconstitutional without seceeding seems like an attempt to have a union and eat it too.

Officials and voters often behave with less honor than that needed for the proper functioning of a liberal republic. No formal constitution can overcome that deficiency.