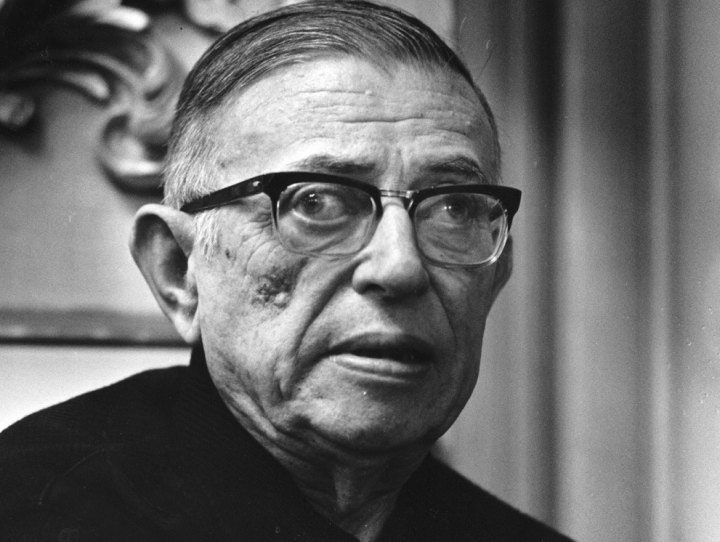

On October 22, 1964, philosopher and novelist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905 – 1980) was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, but turned down the honor — establishing a precedent that should have been followed by numerous Peace Prize winners, including Barack Obama and the European Union.

Only one other recipient of the award has turned it down voluntarily, namely Henry Kissinger’s co-winner in 1973, Le Duc Tho. Four other recipients were coerced by their governments from accepting the prize’s monetary award: Richard Kuhn, Adolf Butenandt and Gerhard Domagk, by the Nazi government, and Boris Pasternak, by the Soviet Union.

Sartre rejected the award on account of having rejected previous honors. In this he was not dissimilar from philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) who refused many doctorates late in life, on the grounds that such awards did an old man no good, and perhaps because he was a cantankerous old coot — a judgment that surely applied in spades also to the later French philosopher.

Sartre is best known for his novel Nausea (1938), his play No Exit (1944) and his treatise, Being and Nothingness (1943). One of his main themes was freedom, a concept better explored at the fundamental level of the individual human being than politically, since he become a “Marxist” of sorts . . . the precise nature of which he elaborated in the Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960). He failed to complete his tetralogy of novels, Roads to Freedom, never finishing the final volume.